Indrani Das, 17, won the Regeneron Science Talent Search this year for her study of a possible approach to treating the death of neurons due to brain injury or neurodegenerative disease. The New Jersey resident also plays the piccolo and volunteers as an emergency medical technician with the local ambulance service.

Half of the winners — and 13 of 40 finalists — were Indian-Americans, notes The Hindu. Twelve have Chinese last names.

Indrani Das won the $250,000 first prize in the nation’s top science competition for her research on neuron death in brain injury.

The prestigious science competition is sometimes called the Junior Nobel Prize.

In the 2016 contest, then known as the Intel Science Talent Search, 83 percent of finalists were the children of immigrants reports Forbes, citing a new study.

Thirty of the 40 finalists had at least one parent who came on H-1B visas and later became U.S. citizens; 27 had a parent who’d been an international student.

Fourteen had parents both born in India, 11 had parents both born in China, and seven had parents both born in the United States.

Other countries of origin were Canada, Cyprus, Iran, Japan, Nigeria, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

The percentage of finalists who are children of immigrants is rising, the study found.

Here are this year’s finalists, the brightest science aces in the nation.

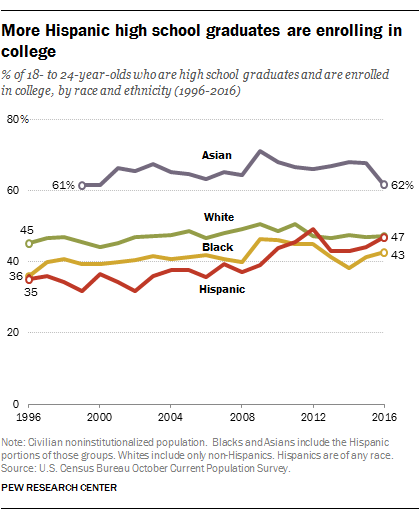

“Only two in 10 Latinos earn bachelor’s degrees, compared to nearly 1 in 3 blacks and 45 percent of whites,” according to a new report from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce,

“Only two in 10 Latinos earn bachelor’s degrees, compared to nearly 1 in 3 blacks and 45 percent of whites,” according to a new report from the Georgetown Center on Education and the Workforce,